HELEN CAPTIVE

Terry stood in the window of the spaceport tower on the rim of the Mount Pavonis caldera. The building was the luxurious residence of the High Companies executives who ruled Mars, and her prison was perhaps the most comfortable quarters she had ever had, but a prison-cell, nonetheless.

She could see the dry, red equatorial highlands of the Tharsis stretching out below. Somewhere over there was the Tharsis Commune, her home since childhood, not far from the headlands of the Noctis Labyrinthus Badlands. From this height, perhaps she could see and take comfort in the glow of the lighted agricultural dome when darkness fell, and the myriad stars came out. But so far, most of the time, the dust-storms hid the surface from her, and the red waves lapped against the mountain’s flanks below like ocean surf. To the south was the volcanic tower of Arsia, rising out of the storms, and to the north Ascraeus. And the greatest of all the topless towers of Mars was Olympus, far beyond the curve of the planet.

All she could see during the long nights were the stars and planets—Earth and Moon like a double-star, Jupiter and its major moons circling each other, and Phobos and Deimos passing each other, one slowly and one swiftly, in opposite directions. And of course, like clockwork, the shuttles coming in to the spaceport from the emerald jewel of the High Mars colony. It had always seemed to her that the lush forests therein had been created as an insult to the Martian miners on the dusty surface.

One thing was for certain: her family in their dry caverns and trundling across the plains in their sand-crawlers would be able to see her prison tower atop the great volcanic shield, if only through binoculars. That was the purpose of her incarceration. The Martians going about their backbreaking daily work, whenever tempted to rebel, fight back, or plan some sabotage, would think of their beloved First Mother helpless in the grip of the High Companies, and the unspoken threat would be that their actions might make her captivity much worse. As a child, she had read the romances of Earth, often featuring a long-haired princess held captive in a tower, waiting for a brave and handsome prince to come and rescue her. She wondered how many such were out there, making plans. She knew of several who would be glad to try, and she feared for their lives. She was the golden bait in the trap.

She went to the mirror and brushed her hair. Terry knew full well that this Alexander creep was somewhere watching her. She had seen the desire in his eyes when he locked her in. For a while, she did what she could to frustrate his designs—sleeping in her clothes, bathing in the dark—but of course he could probably see her in infra-red as well as full light. Eventually, she decided to use his desires against him. Thanks mostly to Loris, she had been trained in close combat, and if he got close enough and she had a suitable weapon, she would happily cut his throat, whatever the consequences.

***

Jay reasoned that Terry would not be in the High Mars colony because Martians were not allowed there. He doubted that she would be kept in some sort of dungeon or the mines to which so many Martians had been sent because of the danger to her life. He knew that high value prisoners had been kept in the Pavonis Tower before. So, he thought she might be there, but had been unable to get a glimpse of her, even with binoculars. He decided it would be too dangerous to move closer to the mountain because of the Quasi-Police traffic in the area; he could do little for Terry if he too was in custody. So, he set down his binoculars and put the sand-rover in gear.

On its six balloon tires, it rolled across the sandy, rock-strewn plains of the Tharsis plateau. In a few hours, he approached the green agricultural dome and entrance lock of the Tharsis Commune, the only portions of the warren above ground. Brandy’s face appeared on the screen, and she buzzed him into the lock. The rover rolled down the ramp into the hangar, the lock shut with a hiss behind him, and he cycled out of the vehicle.

Soon he was in the commune’s big, fragrant dining hall, for dinner with the family. Everyone, of course, wanted the latest news about Terry.

“The authorities will not confirm that Terry is in the tower,” he said. “But they admit she is being held on unspecified charges and is confined in—quote—pleasant or even luxurious, quarters.”

“In other words,” Brandy snorted, “they want us to know where she is but won’t say so.” Brandy, who was Terry’s best friend since childhood, had in fact carried Terry and Jay’s son Shagrug to term and there was no-one closer to the clan-mother.

“Exactly,” Jay said. “I have put in a call to my father in High Europe and I was told he would be responding this evening. We have obviously not been on good terms for quite a while, but I believe he will hear me out. He has no particular loyalty to the other High Families, because none of them do, and he has always been a decent man. Or as decent as one can be when one has more money than God.” There were chuckles at the table.

“I have come up with some disturbing rumours, however. Karil and Loris are missing and so are Aaron Ben David and Chi-Chi Li.” There were gasps and concerned grumbles.

“I’ll ask him about that too,” Jay said. “I’m sure they won’t be in pleasant or even luxurious quarters.”

Throughout the discussion, the table was set, and dinner was served. Little Shagrug sat down next to him, and he put his arm around the child’s shoulders—almost three in Martian years. He was now at the age when he was beginning to seek out his father for particular advice and comfort, and was aware that, although Brandy had given birth to him, Terry was his genetic mother. Jay had been worried at first, wondering if he could accept that everyone in the commune would consider the child his own responsibility. He found that he was not the slightest bit jealous when other clan-members showed affection for him. On the contrary: he was comforted that the boy was loved and cared for by so many. Jay was becoming Martian.

When Shagrug came to him and asked about his unusual name, Jay had explained that Shagrug was the first Captain of Atalanta, and though he was something of a rogue, he had died nobly in the Rings of Saturn, saving other people’s lives. Then he wanted to know about Loris, the second captain, and Karil, whom Jay had grown up with in Lunar L-1. Ever since, he had been coming to hear stories about Jay’s adventures on Earth and in Saturn orbit, and he hung on every word. Though Jay was only one of his clan-fathers, Little Shag was special to him in many ways and becoming more so. Jay had to compare this with his own childhood, in which it was said that “all this” was for the sake of the children, but his own father was cold and critical. Jay was not looking forward to speaking to him again, not least because an interplanetary call was such a frustrating ordeal.

***

Jay was in his room, reading, when the screen chimed, and his father appeared in his luxuriously appointed office, the French doors open behind him to the lovely High British countryside.

“I’m not supposed to be speaking to you,” Lord Coldwell said. “Your friend Ali Karil has murdered his father. I imagine you find that hard to believe, but I have the word of Captain Solla himself. Then, he stole a shuttle and a lot of weaponry and escaped.”

Jay was stunned. For a second, he stared at the English country landscape curving up into the sky outside the big glass doors as his father waited for a reply. He was, however, relieved that Karil was free, and therefore probably Loris as well. As the light-lag stretched on for several minutes, he wondered in passing why Karil didn’t kill that sonofabitch Solla too if he had the chance.

“I can’t believe this.” He told his father finally. “He’s a fighter, but he’s not a killer. I can’t say the word of Armand Solla means a lot to me. There must be more to this than meets the eye. But I called to talk to you about Terry. She’s been arrested. I saw it happen. On the Aphrodite. They held me at gunpoint. Put a gun to my head, Father, as if I was some kind of criminal. We were returning from a diplomatic mission. She’s not a rebel. She’s not a criminal. She’s the duly appointed representative of the Martian people. I can’t help but think she’s been taken as a hostage. You know that’s wrong.”

Now, he had to wait for several minutes for the message to get to Earth, for his father to see it and answer, and for the reply to get back to him. Finally, his father reappeared.

“I don’t like the idea either, Jay. But if such an action has been taken, then the High Families have voted for it, and there’s little I can do. Why don’t you come home? That would make her, and your son, a member of our family. Then I could keep you safe.”

Jay’s heart sank. But he was angry at himself for expecting anything else.

“She doesn’t belong to me, Father,” he said. “She belongs to Mars. Don’t expect me to call again. Jay out.”

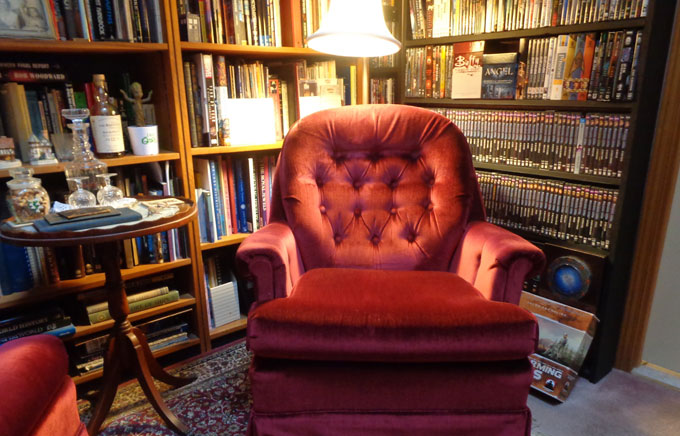

He picked up the book he had been reading and went out into the Common Room. A number of Clan Elders were sitting around the table. Jay sat down and placed the book before him.

“This is Progeny’s journal,” he said. “I propose to retrace his travels, commune by commune, to reinforce his message.”

“That will be exhausting for you,” a clan-mother said, “as it was for Progeny. Eventually, it killed him.”

“I have to do something for Terry. If our friends in the Rebellion and the Galilean turn up, the people may be open to talk of getting her out of there. I’ve just learned that Karil, and probably Loris, are free, which gives me hope.”

“I’ll go with you,” Brandy said. When he began to argue, she insisted, her dark eyes flashing. “Progeny almost went mad from the isolation. Terry would want me to do this. You know she would.”

The very next morning, the rover was loaded with supplies, the oxygenator system topped up, the solar panels checked. Jay paused and turned to the well-wishers.

“I’m not Progeny Brown,” he said. “I’m just a shy bookworm, as I was when I was a child, but I know his words by heart. I’m not the scholar he was, or the poet that Karil is. Terry would be far better at this than I am, but I must try my hand at it because she’s not here. The High Companies think we will go to pieces without her, but we must show them that when Progeny is gone and Terry is silenced, any one of us can take their place and the Martian spirit will thrive.”

There was applause and shouts of encouragement from the crowd. Jay climbed into the vehicle and sat next to Brandy at the front port. The sand-crawler cycled through the lock and emerged into the cold, dry, thin air of the Tharsis. It turned out that everyone welcomed a visit from the foremost expert on Progenist theory.

***

Alexander was the perfect gentleman. He knocked at the door and Terry opened it for him. He entered, followed by a phalanx of sommeliers and waiters bearing wines in silver buckets and fragrant foods on silver trays. Throughout the meal, which was varied and delicious and served with style—Terry thought it compared favourably with the service aboard the Fair Aphrodite—Alexander chatted about the beauties of the solar system he’d seen—the Great African Rift and the Himalayan Range of Earth, the awesome spectacles of the Jovian and Saturnian Systems, the glories of the Mariner Valley and Mount Olympus of Mars. He was one of the few who had travelled to far Neptune, and he spoke of its sapphire blue depths, like a spherical ocean. All the time, Terry was watching the cutlery come and go, hoping she could get her hands on a knife, but the servers were attentive, and everything was whisked away with dispatch.

“Tell me about Progeny,” Alexander asked.

Terry looked askance at him.

“I’m not trying to get you to reveal Rebellion secrets,” he said. “I’m sure nothing could make you do that. It’s just that I’m fascinated by the man and you’re the only person I’ve ever met who actually knew him. Except for Captain Solla, who’s a bit—shall we say—prejudiced.”

Terry chuckled. “I’m sure you’ve read a thousand reports,” she said.

“That’s true. Informative but not revealing. He was born on Earth in the Southern Provinces of the former U.S., the son of a preacher/conman and groomed for the same career. He killed his father, who was apparently a child-molester, for which he was incarcerated at L-2 Prison on the far side of the Moon. He attempted to save the life of the Sultan of High Africa’s favourite concubine, who was pregnant with Ali Karil, for which he was rewarded—if that’s the word—with transportation to Mars.

“In the Argyre Mines, he began to formulate his philosophy. He escaped with Salim Malik and became a rebel, a serious thorn in the side of the Quasi-Police—stealing weapons, blowing up crawler-trains, sabotaging troop carriers, freeing prisoners—apparently copying the French Resistance of World War II. He was in fact a professor of History and used that knowledge to his advantage. He was captured by Captain Solla and then freed again by Aaron Ben David’s mercenaries. He wandered all over Mars in a sand-crawler, talking to miners about his theories of life and love and family—a religious figure despite being an atheist, a politician who despised politics—and pretty much created the Martian Communal philosophy out of whole cloth.

“That’s when you met him, barely more than a child, and eventually became his third wife. When he was driven into exile on Earth, you went with him because you were the only one of his wives able to tolerate Earth gravity. He was already beginning to suffer the effects of years of surface radiation. On Earth, you met the Galilean Free Traders including Ali Karil. Solla imprisoned Progeny again but you and the Free Traders broke him out of the Citadel in Nueva York, and he died free. He passed on the mantle of the Martian revolution to you, and the poet Ali Karil became his chronicler. It’s a very romantic story, but the Quasi-Police dossiers manage to make it sound dull.”

“Dull it was not,” Terry laughed. “But you got one thing wrong already. What is happening on Mars is not a revolution. It’s a rebellion. Progeny always said that a revolution is the turning of a wheel, in which one government is replaced by another which becomes just as tyrannical. Any revolution that obtains power will eventually be faced with another revolution. But a true rebellion rejects government altogether. The only government on Mars, Major, is yours, and we don’t want any of it. The last thing we want is to become you.”

“Interesting," Alexander said. “I think I’m beginning to understand a bit.”

“Then, think about this for a while. Progeny often taught using collections of three ideas, because people easily remember them. Coming out of a coercive religious background, he hated the concept of sin, which he thought was just another way to control people’s behaviour. But once he said there were three actual sins, evil in individuals and even more evil in governments, though government is constantly trying to make use of them. They are ignorance, lies, and cruelty. That comes from the first lesson in our version of a first-grade primer, and so I begin with that. I'm a teacher, you know.”

“Of course you are,” Alexander laughed.

“I know this is a chess-game we’re playing here. You’re trying to influence my thinking and I’m trying to influence yours. This wonderful meal is to make the medicine go down.”

Finally, Alexander took his leave and left, still a perfect gentleman. As Terry prepared for bed, she decided that he was trying to seduce her. She hoped she wouldn’t have to seduce him if that was necessary to escape. It was then that she realized she had neglected to turn off the lights before getting into bed, in front of the mirror. And like most Martians, she tended to sleep in the nude.

***

It was evening when the rover arrived at the Tithonius Commune on the floor of the Mariner Valley. Brandy and Jay were welcomed with open arms. Always glad to see anyone from outside, particularly someone as famous as Jay Coldwell, the family put out a wonderful meal of hearty stew and homemade bread and their own home-brewed beer. First, they wanted to know about Terry. Jay told them how she had been taken by the Quasi-Police on board the Fair Aphrodite and, he guessed, was being held hostage at Pavonis. Everyone was angry and frightened.

“Instant Karma’s gonna get them,” one of the elders said.

Jay glanced up at him. “You’re a Lennonite?” he asked.

“Yes,” the old guy said.

“There are a lot of Lennonites on Mars,” Jay told him. “You can go to Church and sing a hymn,” he quoted. “You can judge me by the colour of my skin. You can live a lie until you die. But one thing you can’t hide is when you’re crippled inside.”

“I’m Desmond,” the old man said. He seemed delighted to hear someone else who knew his scriptures.

“I have another favourite,” Jay said. “There’s room at the top, they are telling you still, but first you must learn how to smile as you kill. You know, Progeny’s ideas were heavily influenced by Lennonism.”

“Really?”

“I was there when he died. Some of us were praying, and one time he mumbled: Now that I showed you what I been through, don’t take nobody’s word for what you can do. There ain’t no Jesus gonna come from the sky.” He laughed. “In fact, there’s a refrain that pretty much sums up his philosophy, if I can remember it: Imagine there’s no heaven. It’s easy if you try. No Hell below us and above us only sky. Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for, and no religion too. You know, he based the Martian calendar we use on a Lennonite idea.”

Everyone wanted to know about that. Brandy smiled and got one of the mothers to get him another beer.

“There were lots of ideas for a Martian calendar,” Jay went on, “but most of them were just variations on the Earth calendar, convenient for Terrans, but completely inappropriate for life here. But Progeny knew that the sun from Mars appears to transit sixteen constellations in a Martian year--Aquila, Delphinus, Pegasus and Andromeda in the northern Spring; Pisces, Aries, Taurus and Orion in the Summer; Monoceros, Hydra, Crater and Corvus in the Autumn; and Centaurus, Lupus, Scorpio, and Ophiuchus in the Winter. He ran across a Martian calendar devised by astronomer Robert G. Aiken at the end of the Nineteenth Century that had sixteen months of 42 sols, which is 672 sols, four more than 668. If in every quarter, you have three months of 42 sols and one month of 41, there’s your 668-sol calendar.”

“It’s perfect,” Reverend Desmond said. “I know there were attempts to create a lunar calendar out of Phobos and Deimos, but it was too complicated.”

“Not only that,” Jay went on. “The same calculation could give you 42 weeks of 16 days. But that troubled him because 16 days is a long work-week—too long to wait for a rest, even for Martians—but he heard a song by John and Paul…”

“Eight days a week.”

“That’s the one. So, he thought we should divide the weeks into half-weeks of eight days—five workdays followed by a Friday holiday for Muslims, a Saturday holiday for Jews, and a Sunday holiday for Christians—but of course anybody could take all three if they liked. That’s why you have a weekend holiday break and a mid-week holiday break.”

“A working-class hero is something to be, isn’t it?” Desmond said.

Jay laughed. “Believe it or not, he came up with this plan on his deathbed, still thinking up ways to make life better for Martians.” He raised his glass in a toast. “To Progeny.”

“To Progeny,” everyone repeated. He set down his glass and his face darkened dramatically. Brandy tried not to laugh. “And now his beloved wife, and mine, is locked up in that tower, alone, and without her family. And I hear Ali Karil, her other husband, is missing. But I have it on good authority that he killed the Sultan of High Africa, his father, and is out there somewhere. If so, you can believe two things: Loris and Atalanta are with him, and they’re already working on a plan to bust Terry out of that place. So, Brandy and I are retracing Progeny’s route to ask everyone in every warren: If we call on you to help, will you do what you can?”

There was a cheer around the table, part angry, part sad, part laughing with joy. Brandy shook her head admiringly. Some time later, they were given a bed in a private room.

“You know what I love about you?” Brandy asked, unbuttoning his clothing.

“What’s that?”

“You're a quiet man, but when you need to, when it’s important, you can talk up a storm. Not everybody with a mind like yours can actually do that.”

“Better than Karil?”

“He re-writes, I’m sure of it.” She pushed him down on the bed.

“Frankly,” he said, “most of the time, when I speak, I’m just remembering something I wrote. So I don’t qualify as a great speaker. But don’t stop doing what you’re doing on that account.”

Her long ebony hair spilled over his body.

***

Dinner with Major Alexander was beginning to be a regular date, and Terry now looked forward to it. She realized that the servers, judging by their Ninja-like economy of movement, were there not just as chaperones for her, but as bodyguards for him.

“Last time,” he said, dishing out some exquisite shrimp no doubt raised on High Mars, “you were talking about how Progeny liked to express his ideas in threes.”

“He liked to joke that we were in a War of the Worlds, and we should stand on tripods. For example, the Fantasy Class, the Reality Class, and the Nightmare Class. The Fantasy Class is this meal I’m enjoying right now and the colony where these shrimps were grown. The Fantasy Class has always lived in castles, behind high walls, or on private islands, but your High Companies went several steps further and created their own private worlds to live in. I must say this is delicious.

“The Reality Class has to work or scheme for a living. Economics is not a tool for them, but a threat they have to deal with. Down here, on the surface, the miners are up against reality every day. On Earth, of course, after you moved out to Lagrange and left the planet to stew in the ecological wasteland you helped to create, it’s worse. Most of Earth is deep in the Nightmare Class, which has always been there too--in the slums, the streets, the garbage dumps, the displacement camps. In Nueva York, the abandoned subway tunnels are infested with gangs of cannibals. I nearly fell victim to one. But their leader had once been a scholar and admired Progeny, so he let us go and took the blood-lord gang that was stalking us instead.”

“My God,” Alexander said. “Why were you there?”

“Long story, but not secret. That was the way into the Trade Tower Citadel, so we could spirit Progeny away from Captain Solla.” She waved her hand as if that was nothing and Alexander gazed at her with wonder in his eyes.

“Next,” she went on, helping herself to Béarnaise Sauce for her asparagus, “is Patriotism, Religion, and the Family. Progeny noticed that political speeches always turned on those three subjects, so he realized they were a three-pronged attack on human emotion in the name of stifling independent thinking.

“In the name of patriotism, perfectly decent people will torture and kill the enemies pointed out by their masters. But religion is its handmaiden. The witch doctor has always supported the war-chief in the end, propping up his authority with divine sanction. Even prophets of peace and tolerance like Jesus and Mohammed and Buddha have been used to authorize torture and rape and mass-murder. Progeny always said that if God really is the creature depicted in the Bible and really authorized the acts committed in His name, He’s a monster.”

She laughed. “That didn’t go over so well at a revival fair in Ohio. But then he said: Despite this, the world is filled with kind and generous people who believe that God is loving and forgiving, just like them. Where has this God come from, he asked, if not from their own good hearts? They have created Him in their image, and they use the authority of Scripture to back up their own good instincts. In the Protestant Reformation, he said, the revolutionary idea was that individuals could seek guidance from the external Moral Authority without the intersession of Church Hierarchy. But Progeny believed that the Moral Authority exists only within us. We might look for enlightenment or inspiration in the words of ancient scholars or living wise men, but if we find Moral Truth it was not in their words, but in our own generous hearts and our own rational minds. This is really delicious. May I have some more sauce?

Alexander stared at her in awe as he handed her the dish.

“But the big nut to crack was the Family. Obviously, the family is not evil—only the kind of family that the Fantasy Class was selling. Could I have some more wine?”

Alexander snapped his fingers and a server topped up her glass.

“Where was I? Oh. Yes. The Fantasy Class has always been obsessed with genetics: race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, hereditary rulership and primogeniture, adultery and illegitimacy, contraception and abortion, Darwinism and Creationism... The whole history of the Fantasy Class is a desperate attempt to legitimize and pass on their status to their natural offspring. When you realize to what extent their power is illegitimate, their authority imaginary, and their property stolen, it’s little wonder. Progeny thought we ought to eliminate genetics as much as possible from child-rearing. We're called Progeny’s children to point out the fact. The matriarchy is part of why that works. Boys of marriageable age move to other communes to choose their wives, and that forms a link between two warrens while reducing the danger of in-breeding, which is endemic in Fantasy Class ruling families, I must point out.”

Alexander smiled and changed the subject. “I found something that may amuse you.”

“Okay.”

“It’s a Quasi-Police tavern-song, and it’s a little rough.”

“Really? Do you think there’s anything I haven’t heard, growing up in a mining colony?”

“All right. It’s called Satan’s Sandbox.” He recited it with an engaging grin:

No fucking air, no fucking heat.

Recycled water is no treat.

The dust gets in your goddamn boots

And even in your pressure-suit.

Please tell me how that comes to pass!

The wind will knock you on your ass

And bury your sand-rover in the drifts.

The sky’s the colour of warm piss—

That’s how the rover smells inside

Before the rescue-ship arrives.

The year is twice as long, you know,

And all four seasons Winter without snow.

And did I mention the Martian rebels

Who come from nowhere and fight like devils?

Make sure you leave when your contract’s gone

Or you’ll be stuck here your life long.

Terry laughed long and loud, and Alexander smiled in what seemed like genuine affection, if not something deeper.

***

The Mariner Valley is so long that twice a day one end is in sunlight and the other in the dark. The winds rush from one end to the other in the morning, and in the opposite direction in the evening. The resulting local dust-storms are not as powerful as the seasonal storms that arise in the Noachis, which often cover the entire planet, but the static electricity caused by the talcum-fine dust may cause a sand-crawler’s lights to flicker and the engines to stall. The best thing to do is to stop and wait until the morning, when the winds blowing in the opposite direction will usually uncover the huge balloon tires. A night on the surface is not a great ordeal for Martians. In fact, it’s their alone time.

When the lights began to flicker and they could see drifts of fine dust burying their wheels, Jay and Brandy stopped in the lee of a crater-wall and switched off everything but the oxygenators, which they powered down as much as they could. In the morning, the way would probably be clear, and they might not have to suit up, go out, and brush off the dust by hand. This would be difficult, because the dust would cling to their p-suits, and cause all kinds of problems.

For now, there was nothing to do but sleep, using as little oxygen as possible and keeping each other warm as the cold night fell. They crawled into the bunk and snuggled down. The interior lights were off, except for a few blinking tell-tales to indicate the functioning of critical systems. The forward port was clear of dust, fortunately, and they could see the stars. Deimos sat almost motionless as the stars drifted by, and Phobos zipped past, racing in the wrong direction across the black sky. It would do so again before morning.

“Do we really have a chance to get Terry out of there?” Brandy asked.

“We got Proj out of the Citadel, and that was as formidable as a medieval castle, with all the Wall Street towers rising out of the sea and a great wall around it. But I’m worried about the Quasi-Police moving her somewhere else if the MLF or somebody gets itchy and starts causing trouble. She’s supposed to be a hostage for our good behaviour and if they think it’s not working, they could ship her off to Venus or God knows where.”

“But how could we possibly storm Pavonis?”

“Well, I’ve been thinking about that. We’d have to attack several places at once to make them too busy to send reinforcements. There are two ways into the Spaceport—above and below. To attack from above, we’d need a ship like Atalanta. But there’s also the elevator up the escarpment. The base at the bottom is surrounded by surface crawlers and tanks. It’s from there that they send them out in all directions across the Tharsis to the lowlands.

“But there’s more. They have two capital battleships here—Grim-Visaged Ares and Poseidon Earthshaker. Then there’s High Mars itself, which has its own defences, in Clarke orbit above the spaceport. Basically, all of their military might is here, both to pacify Mars and as a base to invade the Belt. They don’t need much of a military presence on Earth because there’s nobody on the planet below that can threaten them, and Luna is in their pocket.

“We would have to attack them on four or five fronts and still defend our own warrens. I don’t think much of our chances of actually bringing them down, but we could distract them long enough to free Terry. And I can’t see doing that without allies. If we could get some of the Belters and the Galilean to help us, we might do it. I don’t know where Karil and Loris are; they might be able to convince the Galilean to help out. And the last I heard, Chi-Chi Li and Aaron Ben David were in the Belt somewhere, and I don’t know where they are either. I’m trying to get our own people alerted, without getting them too riled up and going off half-cocked. Karil and Loris, Li and Aaron could help there too. Martians would follow them, and, more important, obey them.”

He found Brandy fast asleep in his arms. He lay silently for a while, smelling her hair and looking out at the stars. In the morning light, they heard sounds and felt the crawler rocking. Outside, they saw another sand-rover being hitched to their own and several p-suited figures brushing the drifts from the tires. Gloved thumbs went up. Their rover was hauled out and after a few hours’ drive both were admitted to the hangar at Melas Commune.

“The people at Tithonius sent us a message that you were coming,” First Mother said. “After the storm, we went out to find you. Coffee?”

“My God, yes.”

The coffee was delicious. “We get it from smugglers,” First Mother said, when she saw Jay’s smile.

They gorged on waffles and syrup, no doubt also from smugglers. The Melas Chasma, Jay guessed, was a relatively easy place for freetrader ships to slip in undetected. Sipping coffee afterwards, Jay answered their questions about Terry, and then spoke up.

“Last night, I understood something about Progeny that I’d never really understood before. Looking out at the night sky, with Brandy in my arms, I felt a deep contentment. Now, I was raised in High England, which is a lovely place, with thatched villages on winding roads and stone-walled sheep-meadows between green woodlands, but it seems cold and artificial to me now. It was designed and built to be beautiful by human minds. It’s a brilliant artifact, but an artifact none the less. But Mars seems to have been here, waiting for us forever. Proj has spoken and written of the spiritual love that Martians have for this place. And last night I discovered it for myself.

“I think, in a brilliant way, Progeny managed to bypass all the superstition and doctrine and go straight to the centre of spiritual belief, which is the heart of being human. He said—I hope I can remember his words—there is such a thing as poetic truth, which is always confused with scientific truth at our peril. Fundamentalists insist that their Holy Books must be considered literally true because the poetic truth that fills their pages is beyond their grasp. They have neither science nor poetry in their souls. They want to pin God to the pages of the law like a collected butterfly. The scientist’s ingrained habit of caution, self-doubt, and insistence on questioning the facts has to bring you closer to beholding the creator’s face than the willful ignorance, arrogant self-certainty, and fascist bullying of the religious fundamentalist.”

Brandy smiled at the idea of Jay pretending to be unsure of Progeny’s words. He never read a word he couldn’t remember.

“The cheetah’s speed and the eagle’s vision, Progeny said, help them to fill an ecological niche unavailable to others. Why shouldn’t the particular gifts of the human species serve a similar purpose? Our outsized brain is meant to be used. Those who think for themselves must be more pleasing to God than those who blindly follow authority. Our nagging conscience is there to be heeded. Those who defy the law when its decrees violate their conscience should be more beloved of God than those who obey such laws. Human sexuality is a gift more subtle and complex than necessary for the simple reproduction of the species. Therefore, expressing one’s sexuality must be more pleasing to God than repressing it. Genetic variations in the human species—skin-colour, special talents, sexual preferences—are congenital and have a purpose. Such people should be sought out and celebrated, their stories heard. Blind hatred of such people must be profoundly displeasing to God.

“But for thousands of years, one creed after another has tried to convince us that God wants us to abandon our reason, stifle our conscience, suppress our sexuality, and exclude the deviant. The conclusion is obvious: religion is the enemy of God. You don’t need the imprimatur of the Almighty to behave like a decent human being because behaving like a decent human being is in your own best interest, but you do need to be coerced by the threat of God’s displeasure to rob and murder your fellow man at the behest of the government. It’s not by accident, you know, that the most authoritarian societies in history have been the most puritanical, and those most tolerant of free love tended to tolerate free thought as well.

“Progeny knew that Mars, like the deserts of Earth that spawned most Terran religions, is a preternatural and awesome place and the spiritual experience is common here. He wanted us to consider such revelations and experiences to be like dreams or the artistic vision—meaningful only to the dreamer, however interesting when shared. He thought all the Holy Books of Earth were simply collations of inspirational stories collected from many sources, and if their compilers could see us persecuting and murdering each other over scriptural minutiae, they would be horrified.”

***

Terry was quite aware that she was being played by Alexander. She was placed in this gilded cage with no books and no screens, and there was nothing to do all day but think, until he turned up with a fine dinner served by attentive waiters. Naturally, she looked forward to it—not least to his interesting conversation.

“I’ve bought a book,” he said.

“Oh. Good for you.”

He smiled at the jibe and took out a thin paper volume. “This is printed on real paper. I guess it was made in some commune.”

Terry took the volume and leafed through it. It was Aphorisms of Progeny. “I know which commune,” she said, “but I won’t name them, since this book is banned. How did you get hold of it?”

He laughed out loud. “Well, they’re banned for those who might be seduced by them. I’m not considered one of those.”

“I see. The law doesn’t apply to the government and morality doesn’t apply to the Church.”

He smiled. It was quite a nice smile and always seemed genuine. “That one’s in there,” he said.

“The Aphorisms are my favourite, even more than The Theory of the Fantasy Class or the Sermons.” It was her turn to laugh. “How he hated that they were called sermons! I told him: you showed up at a revival fair full of Christians, Millenarians, and Lennonites, and told them all about God and Morality. What the hell did you think they were going to call them?” She looked inside. “I like this one,” she said. “Oscar Wilde declared that the pure and simple truth is rarely pure and never simple. I disagree. The truth actually is pure and simple. The problem is that we refuse to believe it.”

“Give me some more.”

“Of course. Give me some more of this wine.”

He snapped his fingers, and the silent server filled her glass. She took a sip, and then another, and read out loud. “For every problem, there is one best solution. This solution is easy to spot. It’s the only one that will not be tried. Or this one: There is a big difference between being willing to die for your beliefs and being willing to kill for them. I’m pretty sure the latter requires a higher standard of proof that you are right.”

Alexander was grinning from ear to ear. “I have my favourites too: If you want to raise literate children, you might just give them a list of the most-often banned books and expressly forbid the reading of them. This will lead them to all the great books of literature. Or: The purpose of politics is to take something away from the person who found it, grew it, or made it, and give it to someone whose only talent is thinking up reasons why it should belong to him instead.”

Terry laughed. “Are you sure you’re in the Quasi-Police?”

“My whole career.”

“Really? You mean those guys who bust down your doors, line everybody up, scare the children, and dump our stuff on the floor, then leave?”

“I’m afraid so.”

“You mean those guys who locked my husband in a sensory-deprivation chambre and tried to scramble his brain? And hounded him across the surface of Mars until he died of radiation poisoning?” Her eyes bored into him.

“I don’t suppose you’ll believe I hate that almost as much as you do.”

Terry took a sip of wine and calmed down. “Try this one: Words are only noises with agreed-upon meanings. And if a word—like God or Nation or Truth—means something different to everyone who uses it, the word has no real meaning and the thing named has no objective existence. It has no intellectual content—only emotional impact. Or: The whole world agrees on what is unethical and always has, but morality is different in different times and places, and it changes from decade to decade with the changing needs of those who make their living from controlling, licensing, or selling forgiveness for whatever they label as immoral.”

Alexander sat back, and his eyes bored into Terry’s. “You really despise us, don’t you?”

She leaned forward and put her elbows on the table. One of the servers moved forward, as if she was about to reach for a weapon, but Alexander raised his hand. Her change of position gave Alexander a fine view of her breasts, but he wasn’t sure if she knew that.

“Why would we not?” she asked. “Your High Companies created a system of residential warrens in a mining-tunnel complex, as a base for sand-crawler exploration over a wide area and transported mostly prisoners and prostitutes to live in it. Each one is as isolated as a Pacific Island. Our family life was modelled on that of certain Polynesian islands before the unfortunate arrival of the Christian missionaries, including a matriarchy to run the place when the men were out at sea. We have no sense of patriotism because we don’t own the land. We love our desert despite its monotony and its dangers the way sailors love the sea, but think of ourselves as figures in the landscape, not its possessors.

“Our loyalty is only to each other. We come from a hundred different religions, but we think of them as personal revelations, not public crusades. With Progeny’s help, we’ve tried to create a society free from the most powerful sources of human conflict--greed, politics, religious strife, and sexual jealousy—which we brought from Earth. All Progeny did was to explain how it could be made to work. If you had treated the miners fairly, as economical partners, there wouldn’t have been a Rebellion, and Progeny wouldn’t have ended up on the run. It was your security forces that drove him from warren to warren, giving him a chance to spread his message. So, if anything comes of the Martian Rebellion, he’ll be remembered for it, but it’s really you we should thank.”

Though she was quite tipsy at that point, he made no move. When he was gone, she felt relaxed and happy. She had a long warm bath—almost a sinful pleasure for Martians—dressed for bed in the low, warm light, and slept soundly. In the morning, she awoke and remembered that she had chosen an extraordinarily revealing nightgown to wear to bed and had a vague recollection of masturbating in the bath. She realized that she had been drugged, displayed herself to Alexander’s cameras, and had in effect raped herself for him.

When Alexander turned up next time, he found her locked in the bathroom like an adolescent girl. “Tell them to bring me what you feed the other prisoners,” she said through the door. “I will never speak to you again.”

***

The rover was welcomed by the people of Capri Commune, who, perhaps inspired by the name of the canyon, had built a collection of domes, not just for agricultural purposes, but for relaxation. Jay and Brandy were treated to a picnic lunch beneath the trees of a green, flowered forest. The foliage blocked the view of the desert outside. It was a welcome break from the cramped and noisy crawler. Their reputation had preceded them by radio and sand-rover, and the whole warren feasted with them. Jay had something special to read afterwards.

“This,” he said, “is a transcript of Terry’s Eulogy for Progeny, just as his ashes were about to be scattered into a dust-storm by Loris. Atalanta recorded the speech for her library, later transcribed by Karil. And I was there, listening. She was standing on top of a crate of machinery, surrounded by damaged ships and noise and people with welding torches, and the place went completely silent as people gathered around her. This is what she said.” In the forest dome, except for the birds and frogs, silence fell over the assembly.

“I don’t know whether Mars will remember Progeny more for the evils he spared us or the gifts he gave us. He wanted to spare us war and tyranny and the other evils that nationalism is heir to, and what he gave us was a particular Martian patriotism, in which we love the land without seeking to possess it. He wanted to save us from ignorance and bigotry and the other evils that masquerade as religion, and what he gave us was a particular Martian ethic, in which we strive to love each other without a mythological mandate. He wanted to spare us the pain and tears that the human reproductive struggle is so often heir to, and what he gave us was a Martian family, in which the young are loved and taught by all without regard to their genetic inheritance.

“Long ago, he saw that the most powerful tool of the tyrant is evil done in the name of good, and the justification it gives to man’s passions. He saw that familial love, freed from the power of the selfish gene, could not be used to make good family men enslave and exterminate the offspring of others. He saw that the love of goodness, freed from the bigotry of myth, could not be used to make moral men torture and immolate believers in other truths. He saw that the love of land and neighbour, freed from the paranoia of the State, could not be used to turn decent men into gang-rapists and mass murderers. He saw that, without these double-edged tools, the mighty could not turn our passions against our reason and make us perform the evil that is in their interest instead of the good that is in ours.

“His body will be part of the dust of Mars, as his heart and soul are a part of every Martian. To forget his teachings, we would have to forget who we are. To dishonour his memory, we would have to abandon everything we know to be true. And if any one of us should, for a moment, forget what he meant to us, we need only reach down with our gloved hand and pick up a handful of Martian dust, and we will remember.”

Jay paused. There was silence, except for a few sniffles and one hearty sob. “That’s when I fell in love with her,” Jay said. “And I wasn’t the only one. She needs us now. She needs us to be strong and brave and, above all, careful.”