You are the seed of life,

Persephone, you are the Spring.

Earth opens before your gentle feet

And the glare of sunlight

Frightens my dark soul, too long interred,

Hermes leads you down the maze of tunnels

And my heart leaps at the sight of you.

And when you go, when you return

To the surface for a season,

When swift Hermes takes your hand

And the Dioscuri lift your train,

Remember Hades, your dark lord,

Kiss his shaggy brow before you go.

He will wait for you.

--Ali Karil

The Dark Lord’s Kingdom and Other Poems

PART ONE:

SEVEN AGAINST EARTH

by

Joseph E. Swift

And now the hour is ripe when all of you—

Whether your prime’s to come or hath gone by—

Must put on strength…

O pluck not out this city by the roots,

Nor utterly destroy it, the prize of war!

For when a happy city sees good days,

Laud and great honour have the god she worships…

Seven champions clad in spearman’s mail

At the seven ports take post.

Aeschylus--

Seven Against Thebes

THE PROFESSOR

Thomas Fell was the first to know that the raiders were coming. He was on the comm, keeping an eye on the camera views and data readouts of the entire Friendship Colony. He could see the lush, forested interior of the revolving central cylinder, the misted and sunlit agricultural toruses where most of the food was grown, the zero-gravity access tunnels in the superstructure, the interior of the ship-hangar, the storage bays where metals and chondrite and rare earths were stored after asteroids had been mined, and the enormous wheels within wheels of the mechanism that kept the colony spinning slowly in the night to create the one-sixth gravity in which the Belter colonists lived.

The comm alerted him to the approach of the ship. At first, he glanced up in fear. Perhaps it was a meteor. But no, the system—though not as intelligent as the freetrader ships he had heard of—was certainly smart enough to tell a ship from a wandering rock. The more intelligent machines were frowned upon in Friendship, for many of his people thought of them as verging on blasphemy. Machines were tools, fit to preserve data, and only Man, in the image of God, should make decisions based on that data.

Still, he would dearly love to speak to a Smart Ship. If God could speak to us through nature, through weather and the movements of objects in the Solar System, then surely He could speak through one of those wonderful human creations. But though Thomas was technically an Elder—the youngest ever—he kept his counsel on such matters.

The approaching ship was a big one and a fast one, already beginning to slow for contact with Friendship. It was not long before the system found the name of the ship in its memory banks. It was Swift-Footed Achilles and came from High America, one of the great Island Three colonies orbiting the Earth-Moon system at L-1. The people of Friendship knew that ship entirely too well.

Thomas slammed the alarm bell and heard the claxon echoing throughout the colony. Instantly, Wilbur Gurney and Beacon Hicks, the High Elders, appeared on screens before him.

“Is it the Achilles?” Gurney asked.

“It is, Elder,” Thomas said.

The older gentleman was clearly worried. If it had been only a meteor, which they could deal with—blow it up or snag it and mine it for valuables—it was one thing. But to face the murderous rogue police of Earth was another. After the first raid, the Friends had complained to the High Earth Council, thinking naively that men in their employ exceeding their mandate and profiting from graft and brutality would be unwelcome news. But the next raid proved that Earth did not care what happened to a small colony in the Asteroid Belt. Indeed, Thomas had realized, they probably preferred their officers to bully and rob the Belters, since they did not have to pay them as much. Besides, the Belters regularly traded with the Galilean Moons and the Martian rebels and thus were considered enemies of Earth.

Captain Cuchillo’s hard features appeared on the screen, flanked on the ship’s bridge by his cruel second-in-command Soldado and the huge and terrifying cyborg enforcer Montana.

“Ahoy, Friendship Colony,” Cuchillo said. “Prepare to be boarded.”

“We are prepared,” said Elder Gurney.

On the screen, Thomas watched the huge Achilles, nearly as big as the colony itself and bristling with weapons, mate with a clang. The three bridge officers cycled through, two of them drifting into the hold and the cyborg walking across the steel deck with his magnetized feet. There were dozens of others on the ship, wearing body armour, strapped in and armed to the teeth. It was clear that they could make short work of Friendship if deployed. No doubt, many of them would prefer to slaughter the colonists, seize everything they owned, and blow the place to space-dust, except that turning up once a year and flying away with the colony’s hard-won metal and volatiles represented a continuous profit with very little work.

Cuchillo studied the cargo manifests on his hand-held device. He spoke into it and a phalanx of semi-sentient robots poured into the hold and began to haul away the tanks and bales of material, to be installed in the Achilles’s capacious hold.

“Next time,” Cuchillo said, “Twenty-five per cent more.”

“We can barely live as it is,” Elder Gurney said.

“You grow your own food, do you not?”

“But there is ship-fuel, wear and tear on the mining equipment and the colony itself. You leave us with nothing but…”

The cyborg strode forward, his boots thudding on the steel deck. His metallic arm shot out and seized Gurney by the shoulder. The Elder winced in pain.

“Perhaps if we take some of your ships, you needn’t worry about their upkeep,” Cuchillo said. “Perhaps if we leave with some of your women and children, there would be fewer mouths to feed. Where are they, anyway? We never see them.”

They were locked away in the Meeting Room, Thomas knew, which was the only interior space that did not appear on his screens. Thomas did not fail to notice the expression on Soldado’s face when the women and children were mentioned. He trembled with the desire to murder the man. For an instant, he was ashamed of the violent thought, but then the shame was gone and there was only rage. Of course, giving in to such a desire would no doubt result in death for the entire colony. He calmed himself, but the desire to do something—anything—remained.

Finally, the hold was nearly emptied, the bulk of the material hard-won by a year’s work stored in the hold of the Achilles. The robots departed.

“We’ll see you next year,” the captain said. He turned and darted through the lock, followed by Soldado. Just before clomping away in his boots, the cyborg dislocated the Elder’s shoulder and tossed him aside. The locks clanged shut, the ship dropped off and fell into the stars. A med-tech rushed to see to the injured Elder. Hicks said to the listening crowds, “Meeting. Now.”

***

The radiation safe-shelter was in the far end-cap—a suite including the meeting room, a theater, and an emergency docking port, all surrounded by heavy shielding. In case of a solar flare or danger from cosmic rays, the people could gather there safely, with the entire colony between it and the sun, the usual source of danger. It might even protect them from the rare meteor strike. The meeting was held in the meeting hall in the round, where the audience would surround the artists during concerts and plays. The crowd sat in a circle, facing inward. Speakers were acknowledged by an Elder and spoke while the others waited their turn. Thomas was there, visibly impatient to be recognized.

“We must do something, or it will get worse,” he said.

“What do you propose, Young Thomas?” Elder Gurney asked. His arm was in a sling. “We can’t hide from them. The Belt is wide, but our power output is obvious for all to detect, unless we cease mining and then we will wither and die. We grow our own food, but we must maintain the colony to live.”

“We could stand up and fight!”

“Ah, to be young again. We have no weapons, and if we did, they have more. And they know how to use them; we do not. Could you pull a trigger and kill a man without hesitation, which is what you would need to do? And if you could, if we all could, what would that make us? And if we become that kind of society, at the expense of our very souls, if we killed them all and made their ship disappear, Earth would hear of it and would come down on top of us, then justify their actions to the whole Solar System. We would vanish from the Belt and their crimes would continue as before.”

“But what will we do if they decide one day that they want our women as well as our goods? You know they think about it.”

Hicks said, “I’ve heard it said that weapons are expensive, but men are cheap.”

“No doubt that’s true in some places in the Solar System,” Elder Gurney replied, “but if we hire men to kill, do we not have the mark of Cain upon us as they do?”

“Perhaps not as much,” Hicks replied. “They are already marked and perhaps if they fight to protect the innocent, they will store up some good works to cancel out some of their sins.”

“And will we still be innocent?”

“Somewhat less, perhaps,” Thomas said. “It is a sacrifice I am prepared to make in the name of protecting our children, who are indeed innocent. And to prevent creatures like this Cuchillo from moving on to prey on others in the future. Would you condemn a woman who killed a tiger, let’s say, in defense of her child?”

“A tiger is not made in God’s image.”

“Really? Are these men made in God’s image? If they ever were, it seems to me they are no longer so. They are worse than tigers.”

“These are all somewhat specious arguments, Young Thomas,” the First Elder said. What if you find men willing to battle for us? Might they not turn around and prey upon us afterwards? We will be just as vulnerable as before. We will still be easy pickings and they will then be in control of Friendship.”

“They would have to be men of noble character, who consider it beneath them to victimize the innocent, who are willing to risk their lives for honor’s sake.”

“And you believe the Solar System is filled with such people?”

“Filled? No. But I believe they are to be found. The Martian rebels are already trained for war and fight every day against the power of Earth in the name of freedom and family life. The Free Traders of the Galilean speak of such among them.”

“The Free Traders are pirates.”

“They are privateers.”

“Because they are supported by the Galilean, which is in competition with Earth. I know they have a romantic image in the popular imagination, but how close to the truth is it?”

“Well, I don’t know. We are Belters. We know rocks and work and space, but we have little contact with the System at large. Perhaps we could ask someone who knows the Solar System well, who has a knowledge of history and a reputation for honesty and ethics. I’m thinking of Professor Kelley.”

Most of the gathering had been content just to listen to the debate, but now Mary Forster spoke up.

“We have dealt with him for years,” she said. “His dealings with us have been honest and fair and he has helped us as a friend. The colony he founded at Titan is the far end of the underground railroad for many of the wretched of the Earth and the downtrodden of Mars. He was also a soldier in his youth and knows about such things.”

Hicks spoke up. “Much of the material stolen from us this day was contracted for him, for the starship he is building right here in the Belt. We will have to report to him that we are unable to provide what he needs.”

“I will go,” said Thomas. “I will point out that our cargo was stolen and ask his forbearance, and perhaps add that another such theft will destroy a loyal and competent supplier to his project forever, necessitating his finding another.”

Elder Gurney laughed. “I know Kelley well. I seriously doubt if you can pull the wool over the man’s eyes, but I imagine he will see the ramifications of our dilemma quite readily. I imagine, too, that he will see the logic in your plan and will not introduce us to a nest of vipers.”

“If you do this,” Hicks said, “what ship will you take?”

“Well, not Barclay’s Bank,” someone said. “We don’t want anyone to think we’re made of money. Valiant Sixty and Liberty Bell seem a bit too militant, don’t you think?”

“George Fox,” said Thomas. “Our first ship and it looks it. Besides, it’s named after our creed’s founder in the Seventeenth Century and that could be a good omen.”

“So,” Hicks laughed, “we’re looking for knights errant and clinging to good omens. So be it, I say.”

“I will come with you,” Mary Forster said.

“But…”

“But what? I’m head of Engineers. You’re a decent pilot, but you’ll need someone to keep that old ship going. You can’t go out into space alone; you’re a fool if you do. Besides, I’ve heard of Professor Kelley, and they say he has an eye for the ladies, even at his age. I will tell him how much I fear for our women and children. It won’t hurt.”

***

The George Fox was becalmed in space. It was moving at great speed through the Belt on the momentum of the fusion drive, but it was no longer able to ignite the drivers. Aside from the verniers that might turn the ship aside or rotate it now and then, it was falling helplessly. Thomas hung over the engine room hatch and peered down into the lower level, where Mary had jammed herself between some cables.

“The drivers won’t fire,” she called up. “They’re built tough because if they did fail it would be disastrous. But we can’t tell them what to do from the bridge comm.”

“Can you jury-rig something?” Thomas asked.

“I’m an engineer, not a magician,”

“I’ve heard you called that.”

“Yes, by people who don’t know engineering.”

She crawled up out of the hole and he handed her a bulb of coffee. “I’ve put out a mayday,” he said, “and it’s likely Professor Kelley would be the closest responder. We’re due to impinge on the orbit of Heracles soon.”

The asteroid Heracles, which ranged through the Belt from near-Earth to near-Mars orbit, was the centre of the Professor’s little archipelago of residence colonies, workshops, warehouses, marinas, and the Wily Odysseus itself, under construction.

It was not long before they heard a beeping on the comm, and an image formed on the screen. It was that of a lovely young woman, but something about her face was clearly artificial.

“Ahoy, George Fox,” she said. “This is Celestial Intelligencer. Call me Celeste. We have your mayday message.” Her voice was soft and soothing, and the slight Irish accent was a nice touch.

“Thank you, Celeste,” Thomas said, marvelling at the perfect lip-syncing. The slight imperfection of the image, he realized, was programmed on purpose, lest someone mistake her for human.

“May I connect with your comm?” she asked.

“Of course,” Mary said.

Lights flickered. “I see the problem,” Celeste told them. “You were on the way to visit the Professor, I believe?”

“Yes, we have something important to discuss.”

“You can do that in person,” Celeste said, “away from prying ears, while we see to your ship. There are a number of other small problems that could use some attention, as well. She is a well-built ship, but quite old now. Hold on and I will connect you to the Professor.”

“Thank you, Celeste,” said Mary. “I love your name.”

“Thank you. The Celestial Intelligencer was published by Francis Barrett in 1801. It was a grimoire, much of it taken from Cornelius Agrippa, archivist and historiographer to Charles V, who was mentioned in Marlowe’s Tragicall History of Doctor Faustus, in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The Professor has leather-bound copies of all these in his collection.”

“Fascinating.”

Thomas saw Mary slightly unseal her shipsuit. He was a bit shocked, actually, but he said only, “You have a grease spot on your cheek. Let me wipe it away.”

She smiled warmly at him. “You’re such an innocent,” she said. “To some, it’s a beauty mark. Trust me.”

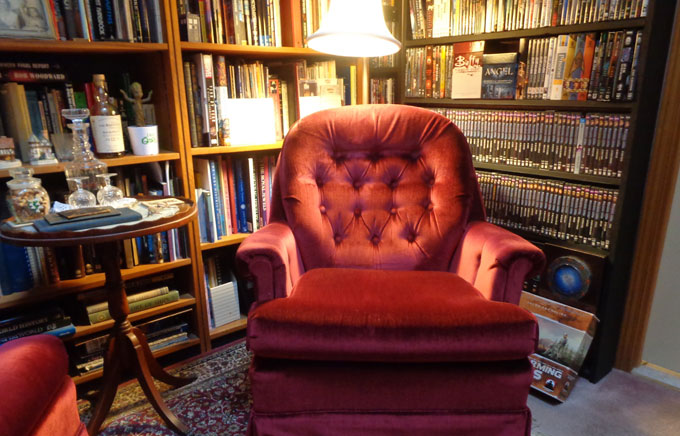

The Professor appeared on the screen and smiled broadly at the sight of them, grease spot and all. Even sitting in a chair, you could see he was a tall man, and his curly red hair and beard gave him a decidedly Viking look. Behind him, half a dozen cats lay on haphazard piles of books, overflow from the crowded bookshelves—not only tapes and discs, but paper books bound in leather. According to rumour, many of these had been looted from the ruins of the Nueva York Public Library.

“Is that Thomas?” Kelley asked. “I remember you from the delegation a few years ago.”

“Yes, it’s nice to see you again, Professor.”

“And who is this?”

“Mary Forster,” she said. “Chief Engineer.”

“Well, if you two have come all the way from Friendship in that little…stout ship, you could probably use a cooked meal and a real bed. We can certainly offer that to you.”

“I’d be delighted, Professor,” Mary said, and there was a look in her eyes as if she had been given a new impact wrench.

“Excellent. Celeste will bring you in.”

He rung off and they felt the Celestial Intelligencer hovering over the George Fox and clamping it tight. There was the roar of drivers that they had sorely missed, and they sped off into the stars.

***

Thomas and Mary gazed wide-eyed at the Odysseus site—the marina with many ships of freetrader, runabout, cargo, and repair planforms moored about a brilliantly-lit sphere that was obviously a spacer’s dive, a huge cargo dump of asteroidal metal beside a foundry ablaze with internal light, the monstrous keel and antimatter-driver assembly of the future starship itself, and a revolving habitat that dwarfed Friendship, even if you did not count the mirrors and disks and rings that surrounded it. And dozens of roustabouts zipping about in flyers.

Celeste mated with the habitat, a Stanford Torus design, and they emerged from George Fox and took an elevator to the rim. The face of Celeste appeared on a series of screens in the corridors and the elevator and the quiet tree-lined street onto which they emerged at last, to show them the way. Thomas wondered what other duties the ship was attending to simultaneously in the complex. They rang the bell and the door opened to a calico cat, who darted away down the hall, then paused to look back at them to make sure they were following. They passed through a series of carpeted rooms with antique furniture everywhere, always clustered about a bookcase. The Professor rose to his full height as they entered the obvious sanctum sanctorum, and he embraced them with his long arms.

“Thomas? Mary? So nice to see you. Dump a cat and have a seat. I imagine that little trip down the gravity well after your voyage must have been tiring. I can fix you up with rooms near the rooftop, where the gravity is a bit less. Can I offer you a small libation?”

“I wouldn’t say no,” Thomas said.

“You could indeed, Professor,” Mary said with a warm smile. Thomas thought she was already flirting a bit too much. The Professor poured three glasses of something with a beautiful red-gold color, a delicious fragrance, and a warmth that slid down Thomas’s throat like a sweet dream. It drained the tiredness from his bones, and he settled back in his chair as a Persian cat hopped up on his lap.

The Professor set down his drink and picked up a cat himself. “So, what seems to be the problem?”

Thomas felt his tongue loosening as relaxation came over him. “Well, to begin with, Professor, I have to report we are unable to provide the order we contracted for. I apologize profusely for…”

The Professor waved his hand. “What’s the problem? Equipment failure? An asteroid didn’t pan out? It wasn’t claim-jumpers, was it?”

“In a way, Sir. We had sufficient materials to fill the order. But they were stolen.”

The Professor seemed stunned. “Stolen? By whom?”

“By the crew of the Swift-Footed Achilles, under Captain Cuchillo of High America.”

“Celeste?” Kelley said and a screen swung in front of him with a ship’s plans on it. “That’s a gunship,” he said. “Bristling with armament. It is indeed from High America. They’re supposed to be patrolling the Belt, not raiding the Belters. It’s a flagrant violation of Interplanetary Treaty. But they’ll deny it, won’t they? Even colonies that are well-armed and trained to fight would not last long against such a ship.”

The dark look that came over his face made his guests feel like cowering. “This is monstrous,” he mumbled. “It’s why I left the Terran military years ago. I could see this sort of thing coming, and not just on Mars either. That’s one of the reasons I founded Nova Terra, out in the Saturn system, far away from Earth.”

“They have raided us two years running,” Mary said, “and they promised to come back. They left us with virtually nothing to show for the year’s work.”

“We can’t fight them,” Thomas added. “We have no weapons. We wouldn’t know how to use them if we did. And violence, even in defence, is against everything we believe in.”

“Of course it is,” the Professor said. “And they know that too.”

“We may have to close down our operation and break up the colony,” Mary said, “look for jobs on Ceres or somewhere, abandon our home…”

The Professor looked into her eyes. “This is not going to happen, My Dear.” He fell into thought. “I suppose,” he said at last, “it is also a violation of your oath to hire others to fight on your behalf.”

“It probably would be, but the vote was not unanimous. Many thought that protecting our families would justify such a compromise .”

“Well, I’ll tell you something, Thomas. These men will not stop with theft. They will become violent sooner or later, toward you and your loved ones. If the High Companies do not pay the price for this in system-wide condemnation, at the very least, the problem will grow. The whole Belt may be in danger, and the Solar System itself thrown into turmoil. It will be Earth versus the Galilean, and Titan will become involved. And we are an antimatter power. Such things always begin with individual greed and end in war unless someone puts a stop to it. Celeste?”

“Yes, Professor.”

“Send a recording of this conversation, coded Galilean High Security, to Atalanta.”

“I have already begun the process, Professor.”

“Why so promptly?” He laughed.

“Because I saw the look on your face, Professor.”