Earth too is hungry

For his message, but some will

Seek to silence him.

"It's happened before." Terry said. "He needs rest, that's all."

"It looks like Martian Fever," said Shagrug.

"It's related. He was exposed to surface radiation for a long time during his wanderings. And before that, his health was severely compromised in Quasi custody. It comes and goes. Exhaustion or stress will bring on an attack, but he recovers after a few days rest and then he's fine for months."

Progeny slept as they moved on, more slowly now than Aaron would have liked, following the meandering course of the Ohio River. Aaron would remain with them through Ohio and not leave until the outskirts of Pittsburgh, for there were troubles all the length of the river. If Cincinnati joined the alliance, would Columbus join too? It was halfway between Cincinnati and Cleveland, the latter already in the alliance because of its location on the shores of Lake Erie. Or would the bulk of Ohio join the nearby Commonwealth of Virginias and Carolinas, thus forcing Cincinnati to join Indiana and leaving Cleveland isolated with its back to the sea? No one knew. Once the travellers had reached Pennsylvania, however, they would be out of the war zone, as the North-eastern part of the continent had been thoroughly dominated and pacified by Quasi headquarters in Nueva York.

***

The rover sat parked in a clearing by the road, and the hummer was hidden off to the side. Two of the soldiers were on guard, and two were asleep inside the rover, but Aaron and the spacers sat around the campfire. They heard the click of a rifle cocking, and the guard's challenge: "Halt! Who goes there?"

Aaron and Shagrug leaped to their feet, weapons in hand.

"Please don't shoot," said a tremulous voice from beyond the edge of the light. "We just want to speak to the Martian teacher."

Aaron glanced at the rover. "Atty?"

"No weapons, Aaron. And though he is frightened, the man speaks the truth."

"Let them through, Vasquez." Aaron holstered his weapon as a dozen people, many with hat in hand, drifted into the clearing. "We have crossed the river from Louisville," said one who seemed to be the leader. "Rumours about you are all over the countryside." Aaron and Shagrug looked at each other and frowned. "We don't know whether you're preachers or revolutionaries, or what. One of you is called Master or Teacher, or even Avatar. We’re hoping to hear him speak."

"I'm afraid he's too ill to speak to you at the moment," Terry said. "But I can..."

"Sit down," said Progeny, appearing at the rover's hatch. Terry ran to support him as he stepped down. "We don't have much food or..."

"We don't need food, Teacher," a teenaged boy piped up. "We need the truth."

"We don't know much about you," said a woman. "But we knew the Martian family at New Planitia. They would come into Louisville to trade for supplies sometimes. We were told they were evil: child-molesters and devil-worshippers and God knows what all. But we knew it was all lies. They were the best neighbours you could ask for. Helped build our house. All we know about you is that they loved you, and they said you always tell the truth. We just want to ask you some questions, and then we will go away. If you don't mind."

Progeny gestured for them to sit. They sat on the ground and Progeny sat gratefully on a stump, Terry curled up at his feet. "I don't know if I have much truth to give you," he said, "but if you ask my opinion on any subject, I will have the common courtesy to give it to you honestly, or I will tell you I do not know the answer."

"That's all we ask."

"Are you a preacher?" the boy blurted out. "Is this just another religion you're selling?" A woman shushed him.

"Sorry, Master," she said. "There is so much fighting between different cults hereabouts..."

"The boy should speak his mind. The answer is no, I have no religion to sell. In fact, I have no opinion on the religious beliefs of anyone, Martian or Terran. Neither I nor anyone else on Mars gives a damn what people believe, as long as the decisions they make are rational and do not put themselves or others in unnecessary danger. As far as Martians are concerned, religious experiences are very much like dreams--meaningful and important, but only to the dreamer.”

Shagrug and Aaron looked about in consternation as more figures emerged from the forest. There was a sizeable gathering now. For his part, Karil was happy to see Progeny looking so well, and he sat down to listen with the others.

"What is your religion, then, Sir? If that's not too personal a question."

"I do not have one. I stopped believing in God when I was twelve years old, and I have never found any evidence that would cause me to embrace any religious tradition."

There was a gasp. Perhaps they had expected him to say he didn't know, or that he believed in some spirit of good despite the evils of this world.

"I studied the religion I was brought up in, namely Christianity, and found nothing to support it outside of the Bible. Then I studied the Bible and came to the conclusion that it was a collection of myths. Later on, I understood that its compilers never actually intended for it to be believed as objective truth; they were merely assembling a great collection of spiritual tales. I've read the original versions of many of those tales from Egypt, Babylon, even India. The compilers changed a few names and details, mixed up a few stories by mistake, and tried very hard to make them consistent with each other, but in my opinion their intent was only for readers to ponder the nature of good and evil, and to think about themselves and the meaning of their lives, which is the most any author can ask from his readers. If they could see modern fundamentalists killing each other over mistranslated minutiae and insisting that every word be taken as unquestioned objective truth, I think they would be astonished and saddened.

"Then I began to investigate all the other religions and came to the same conclusion about them. To debate whether some miraculous event actually took place, or whether an intelligent creator of the universe actually exists outside of the human mind is to miss the point entirely. It is only priests and rabbis and mullahs who insist you believe what they say without question. The real point is to read or listen to the poetry of sacred works and ponder its meaning.

"Its meaning, and its message, universally, is that treating each other with compassion and kindness, and dealing with others fairly and honestly, and loving somebody or something more than yourself is the only way to live a good life. You don't need the imprimatur of the Almighty to behave like decent human beings because behaving like decent human beings is in your own best interest. But you do need to be coerced by the threat of God's displeasure to do that which is not in your own best interest: namely, to rob and murder your fellow man at the behest of the authorities. Does that answer your question?"

The strangers remained for a while, and asked more questions about the murdered family, about Martian society, about Progeny himself. At first Terry tried to tear him away from the conversation, on the grounds that Progeny was ill, but he waved her away. In fact, the man seemed to grow stronger as the evening stretched into night, and then into early morning. Karil watched and listened in awe.

***

Progeny had returned from the darkness, and his condition improved as the rover made its way through the war-torn countryside of Ohio. Children and adults alike ran out to see the unusual vehicle pass by, and as time went on more and more of them seemed to have heard of Progeny. Crowds gathered about the rover at towns and intersections, and it was forced to stop. Townspeople appeared, just to sit and listen to Progeny speak. Aaron fretted and Shagrug scowled, but Terry was overjoyed to see Progeny recovering so quickly, and Karil was as eager to hear him speak as the locals were. Years later, he would hear or read the words of Progeny, usually misquoted and always misunderstood, and he would feel gratified that he had been there at the historic moment. At first, he would try to correct such records, as well as he could remember, but eventually he gave up.

They came upon a collection of carts and caravans and learned that a kind of travelling tent-show was following the same route. Shag and Aaron were horrified at first, but then they decided that the rover would be less conspicuous from orbit in a collection of other vehicles. As for Progeny, he seemed quite at home: there were carnival barkers and snake-oil salesmen of various sorts, which he found fascinating, and there were nightly debates on philosophy and religion in which the arguments were vociferous, yet surprisingly tolerant.

***

Outside of Cincinnati, Progeny spoke to a large crowd in an open field. Someone had asked him to share his revelation.

He shook his head. "Anyone who comes to you with his own personal revelation should be listened to politely, for he may be entirely sincere, and you may learn something. But his revelation must mean nothing to you. Thomas Paine, one of your founding fathers, pointed out that second-hand revelation is only hearsay and no one who has not received the revelation directly is obliged to believe it. Why should the certainty of your belief mean anything to me? Why, in fact, should the belief of millions all over the world mean anything? I can't be entirely certain of the evidence of my own senses; why should I believe what you say about yours? And the Bible, though I love it as a book of poetry, is hearsay several centuries removed.

"Paine, incidentally, was not an atheist; he wrote his religious tracts to defend the concept of God from the atheism rampant in a revolutionary France bled dry by a corrupt Church, and those who have condemned him for it since have unwittingly or otherwise declared themselves on the side of that corruption. This is the usual way of such people; when someone is condemned as the enemy of faith or freedom or democracy, pay attention, for he may in fact be that idea's only real defender. Paine considered religion a sort of blasphemy, which trivializes the beauty and wonder of creation by subverting it to the purposes of the state.

"For the life of me, I can't imagine why intelligent, reasonable adults will not accept the fact that they are nothing more than blips in the timeline of the universe, here today and gone tomorrow, and that their only survival is in the respect and pleasant memories of the people whose lives they have touched during their brief tenure on the planet. Instead of helping their neighbours and planting flowers and playing with their children, they kill their neighbours and trample the flowers and terrorize their children in the name of some mythical god mentioned in a book written by superstitious persons in a cruel and bloody century long ago."

Shagrug and Aaron stood off to one side, ready to intervene should the crowd begin to get ugly. It did not. It listened politely to his message, as he had suggested, and went away, except for a few people who came to him afterwards to ask further questions.

"I can't believe they're not trying to string him up," said Shagrug. "He's contradicting everything they've ever been told."

"The people who told it to them," Aaron said, "have turned out to be hypocrites and con-men and murderers. But what he says doesn't contradict what's in their hearts. I think they've had it up to here with being told what to believe; they came to hear what he believes, and he's telling them, without insisting that they believe the same. I think they appreciate it."

***

In a meadow somewhere between Dayton and Springfield, the locals spread a feast for the occasion and the gathering turned into a picnic. Someone asked Progeny about Jesus.

"The character we call Jesus," he said, "is a sun-hero, of which there are many in mythology, all over the world. Whatever his name, he is born of a virgin at the winter solstice, performs miracles like multiplying food and raising the dead, is crucified or hung on a tree, dies, descends into Hell, and is resurrected at the vernal equinox. In mystical tradition, the ecliptic and the equator form a cross, and at the equinox the sun is motionless on this cross for three days. Since the entire story is symbolic of the passage of the sun through the signs of the zodiac amid the change of seasons and the re-birth of life each year, this is how the tale must end.

"But the New Testament's example of the man Jesus as a perfect Christian human being works perfectly well, or even better, if you do not believe in his godhead; after all, it’s pretty easy for God to be perfect, but for a simple carpenter, it's a major achievement." Laughter rippled through the crowd. "And it works equally well if you do not believe in his existence at all; though we cannot be certain the man ever lived, the sayings and stories attributed to him make up some of the most valuable philosophical discourse in Western literature."

"You don't believe in the Gospels, then?" someone called out.

"You mean the four that were declared truthful by the early Church Fathers, as opposed to the dozens that were not? I believe there is such a thing as poetic truth, which is always confused with scientific truth at our peril. Characters like Jesus and Odysseus, Hamlet and Faust, Sherlock Holmes and Frodo Baggins continue to live because they convey to us certain poetic truths about the human condition; they offer us inspiration and consolation, they provoke wonder and admiration, and they encourage us to think about who we are and how we should behave as human beings.

"Fundamentalists do not want us to wonder who we are and think about how we should behave; they want someone in authority to tell us these things. They demand absolute moral guidance from scripture because they lack the courage to make their own moral decisions and the generosity of spirit to trust the moral decisions of others, and they insist that scripture be taken as literal truth because the poetic truth that fills its pages is beyond the grasp of their limited imagination.

"We human beings, with our oversized brains, are decision-making animals. That is how we managed to survive, without fang or claw, on the African savannah; that is how we survived in our increasingly overcrowded and chaotic cities; and that is how we will survive for the rest of our existence, on and off this planet. For this, we need reliable information. We live on truth, as surely as we live on food and water. Those who would proffer a lie, no matter how lovely, instead of the truth, no matter how ugly or terrifying, are people who wish to keep the decision-making power in their own hands. And those who claim their authority comes from the source of all goodness, and yet behave with no more generosity of spirit, concern for the individual, or restraint of their own physical and political appetites than any secular tyrant, have perpetrated a monstrous hoax upon humanity."

Shagrug stood beside the rover, keeping his eye on the crowd. A young child came up and looked quizzically at the vehicle. "Is that the Teacher’s car, Mister?"

"Yes, it is. Her name is Rover." Shagrug reached up and scratched the metal beneath the forward engine housing; Atalanta rocked her wheels back and forth to make the segmented vehicle wriggle with pleasure. The girl’s face lit up with astonishment and joy, and she threw her arms lovingly around one of the huge tires. Atty purred loudly.

"The Bible," Progeny went on, "is a moving, thought-provoking, and beautifully-written book. It’s a pity that so many Christians have so little respect for it. To insist on its literal truth is an insult to the monumental effort that went into collecting so many spiritual tales from so many civilizations. But fundamentalists have neither science nor poetry in their souls and can’t accept the mystery, tragedy, or beauty of existence; they want to pin God to the pages of the Law like a captured butterfly. Even if, despite the lack of evidence, you believe in your heart that some sort of divinity exists, you must see that the scientist’s habit of caution, self-doubt, insistence on questioning the facts, and tolerance of opposing views will bring him closer to beholding the creator’s face than the wilful ignorance, arrogant self-certainty, and fascist bullying of the religious fundamentalist."

***

Outside of Columbus, they came upon a revival fair. Dozens of tents had been pitched and there were speakers and preachers of all sorts. Shagrug and Aaron were horrified and urged Progeny to move on, but it was out of the question: his arrival was already creating a sensation, and people gathered around the rover. The organizer of the fair welcomed them enthusiastically and was extremely anxious to have Progeny speak.

They were led to a huge tent, which quickly filled with people. As he spoke, preachers and ministers from other tents began to file in and stand in the back rows; Shagrug eyed them with nervousness, but Karil was fascinated with the entire process. He knew that this part of North America had always been a gathering place for cults and sects. Indeed, it was the religious freedom of the American colonies that drew Quakers and Shakers, Mormons and Amish and Puritans of all sorts to set up communes in the area. And since the collapse of continental government, the place had come to resemble the Roman Empire, in which mystics and Gnostics and heretics had battled fiercely for dominance, condemning each other's gospels at sword-point.

Progeny ignored the podium and sat on the steps of the stage as children gathered around him. Once again, he had turned a formal gathering into an intimate chat. Karil, sitting down front with the other young people, found Progeny looking into his eyes now and then. The impression had been growing on him that Progeny was somehow speaking directly to him, though it may have been only a side-effect of his charisma--perhaps everyone felt the same.

"Everyone here knows it’s wrong to cheat your neighbour, to take advantage of those in your power or your care, to harm others simply because you have the power or the strength to do so. You don't need an external moral authority, supernatural or otherwise, to tell you what is good and what is evil. But there are those who do not want you to trust your own moral compass, even though in the final analysis it is the only one you can trust."

Someone spoke up: "Are you telling us that we have to make up our own moral code, our own religion? Isn't that dangerous? Won't people tend to believe what they want to believe?"

"Following someone else's moral code is also dangerous. Theirs can be as self-serving as yours. And if they have what passes for moral authority, it will be difficult for you to listen to your own conscience. Besides, you are already picking and choosing what you want to believe out of the religious traditions you grew up with. You always have. Christian, Jew, Muslim, Buddhist--it's all the same; people believe what they can and ignore what they cannot. Whatever they agree with, they believe is the word of God; whatever they disagree with must have been a later, human addition.

"Like any collection of myths, the Bible is filled with slaughter and horror, revenge and suffering. The God depicted there is a stern warrior, cruel and arbitrary in his justice. You have been assured that sinners and unbelievers alike will be tortured in Hell forever for following instincts God gave them in the first place. Jesus himself is tortured and dies in despair, accusing God of abandoning him. The Apocalypse is filled with dire warnings of war and disaster. It's no wonder that history itself is replete with murders and cruelties in the name of God. If God really is the creature depicted in that book, and if he really authorized the acts committed in His name, He is a monster."

A shocked murmur drifted through the room. Those in the rear protested, those in the front shouted them down and bade them listen.

"Despite this," Progeny went on, "the world is filled with kind and generous people who believe that God is loving and forgiving, just like them. Where has this God come from, if not from their own good hearts? They have created Him in their own image, and they use the authority of the Bible to back up their own good instincts, ignoring everything that does not fit into their own concept of divine justice and mercy--just as so-called religious leaders have used the authority of the Bible to back up their own political and economic agendas, ignoring even the most simple and obvious moral truths in that book.

"In the Protestant Reformation, the revolutionary idea was that individuals could seek guidance from the external Moral Authority without the intercession of Church hierarchy. I am telling you that the Moral Authority in question exists only within yourself; you may seek enlightenment or inspiration in the words of ancient scholars or living wise men, but if you find moral truth it was not in their words, it was in your own generous heart and your own rational mind."

"I don't like the looks he's getting from the back of the room," Aaron said. "You can disagree with these guys on the details but declaring them unnecessary is another story. I wish I could go all the way to Nueva York with you, but I can't abandon my commitment to my employer without..."

"Don't worry about it," Shagrug said. "The fact is, rolling into Nueva York under military escort would attract way too much attention anyway. The Quasi don't care much about the religious quarrels here, but a half-dozen armed soldiers from Chicago Territories would pique their interest, to say the least."

Aaron and his troops parted company with them at the junction of the road to Cleveland.

"This will take you into Pennsylvania near Pittsburgh," he told Progeny. "I don't know if your reputation has spread into the North-eastern States, but for God's sake, Proj, try to keep a low profile."

Shagrug snorted and Aaron glared at him.

"Rumour of your passing may not have reached Nueva York--the people there never paid much attention to anything that happens on this side of the mountains--and if you can keep your mouth shut for a few hundred kilometres, you may be able to blend into Nueva York traffic without trailing a circus parade behind you. All right?”

There was a chorus of thanks and embracing all around. Aaron and Vasquez and their men climbed into the hummer and headed north. At the wheel of the rover, Shagrug watched the hummer vanish over the hill with a sense of foreboding. Progeny had progressed from talking political dynamite to talking religious dynamite, and he was seriously considering binding and gagging the man in the trundle-bed.

The rover shifted into gear and set off through the rolling countryside toward the new-growth forests in the foothills of the Appalachians.

***

The downpour was so powerful that the travellers could barely see the forest outside; only the occasional flash of lightning revealed the wind whipping the trees and the flooded Ohio River cascading over the ruins of a bridge. The rover, attempting to ford the river, had sunk wheel-deep in the mud, and the waters were washing over it with tremendous force. Shouted orders were lost in the howl of the storm as they tried to attach cables to the rover's front end.

"This goddamn thing," Shagrug bellowed, "was designed to cope with every possible terrain but mud. Those tires are great for rocks and sand, but every turn is creating more suction and sinking us deeper in the hole." He waved Karil back and the boy slogged off through the waist-deep flood with a cable coiled over his shoulder, peering through the night and driving rain to see if he could find a tree sturdy enough to attach the pulleys.

He scrambled up the bank and pushed through the undergrowth, his eye on a massive oak he had glimpsed for an instant--only a few meters from the river's edge. The soft ground sank beneath him, and he fell forward into a stinking pool. In a flash of lightning, he stared into the eyes of a rotting human corpse. He cried out and scrambled back out of the pool and flattened against the tree. Another flash revealed that he was surrounded by corpses, washed out of a shallow mass grave by the torrent and tumbled across the soggy ground. There was a third flash and he looked up to see a man standing over him, his face covered by a bandana, his powerful figure clothed in military camouflage, and a rifle in his hands.

Karil cried out in surprise. The man reached down from higher ground, grabbed his hand, and yanked him up out of the mire. He pulled down his bandana and shouted in the boy's ear.

"You all right, Lad?"

Karil panted, his heart pounding with relief.

"Yes, I think so."

The man looked down at the corpses. "The battles were terrible in this district," he shouted. "We'll have to come back when the storm is over and give these poor devils a Christian burial."

They slogged back to the rover and found a second stranger, covered in a dripping slicker, bent over the wheel. "By tomorrow the river will be down," he shouted to Proj and Shag, "and the mud will be dry the day after. A few men with shovels and a couple of West Virginia mules--no offence to your fine horses, Ma’am--will have you out in a jiffy. You’re welcome to come back to the farm and dry off, get some good food in your bellies and a night’s sleep in a bed that don’t move all the time. Put your horses up in a proper stable too. What do you say?"

"Atty..." Progeny began as he turned toward her.

"She’ll be fine," Shagrug interrupted, slapping the side of the rover with a clang. "Just like the man said." Atalanta remained silent.

"Good. We don’t get many visitors out here. I’m Cavallo. This is my foreman, Messer."

"I’m Proj. This is Terry, Shag, and Karil."

"You’re the outworlders they talk about. I thought I recognized this Martian design. Fine vehicle, as long as you stick to dry terrain. Well, let’s get you dry as soon as we can, eh?" They followed the strangers to their vehicle, parked on a muddy forest trail not far away, Karil and Terry leading their horses. It was a troop carrier, old and rather beat up, and there was plenty of room in the back for Proj and Shagrug. Cavallo climbed into the front passenger side and Messer slid in behind the wheel, thrusting his rifle into a carrier on the side of his seat. Karil and Terry swung up into the saddle.

"Will you kids be all right back there?" Cavallo shouted.

"We’ll be able to follow you if you move slowly enough."

"Okay. But watch out for tigers."

"Tigers!" Karil said.

"Wild animal farms all over Florida," Cavallo said. "Flooded out when the coast flooded. Lots of animals escaped and bred wild and made their way up the Appalachian ridge. Some of our cattle were killed by a tiger last week; he was spotted in this area, and we went after him, got caught in the storm, like you."

The procession moved out through the forest. In less than an hour they had turned down a farm road flanked by orchards and cattle-fences. The driver spoke on a radio and massive gates opened before them. They pulled into a courtyard and came to a stop in front of the house. The yard revealed by the light pouring from the windows seemed more like an English country estate than a West Virginia farm--there were stables and garages and tall trees hanging over the ivy-covered walls.

A groom appeared and promised to see that the horses were taken care of, and they followed the host into the front hall, where a butler took their dripping outerwear. They were led into a vast hall, where the eyes of mounted animal heads seemed to wink at them in the flickering light of a roaring fire in a fieldstone fireplace, and huge comfortable leather sofas flanked a bear rug. Their host yanked on a bellpull and in a moment a servant appeared, wiping her hands on her apron.

"Six for dinner tonight, Maria," he said. She vanished with a silent nod, and he broke out the port. After filling glasses for all, he raised his own. "To the Man from Mars," he said. "And his effort to bring civilized thinking to this planet."

***

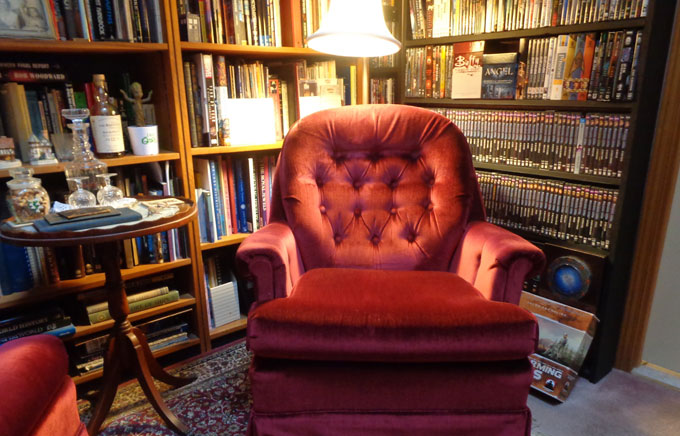

After dinner, somewhat groggy from the venison, the excellent wine of his host's cellar, and the liqueurs afterwards, Karil stumbled off to bed, leaving Progeny and Cavallo in the library, still deep in conversation about the history of the Christian Church. Karil stripped off his ship-suit and donned the silk pyjamas left for him, then slipped into the canopy bed. He felt lost at first in the huge bed, after the cramped bunks of the rover, but soon exhaustion took control of him. How was Atty doing, he thought, as he dozed off. Poor Atty, alone in the night.

He slept fitfully, his rest disturbed by dreams of grinning death's heads and rotting corpses. It seemed that this planet was littered with the dead. They peered at him from behind the controls of gunships and from the handlebars of barbarian motorcycles. They lay in dreadful piles in peaceful farmyards and in stagnant pools beneath great oak-trees.

Karil sat up with a shout. The final image of the dream remained in his mind, including a horrible detail he had not noticed before: many of the corpses in the pool near Atty's location were not those of soldiers; they were exactly like those in the farmyard of New Planitia--women and children, tied hand and foot.

He was blinded by light and deafened by the roar of engines outside his window. He leaped from bed and snatched at his clothing, but the door flew open with a crash and Messer entered, his weapon trained on Karil.

"Come along, lad," he said, and gestured with the barrel.

Karil put his hands on his head and marched down the stairs and out into the courtyard. Proj and Shag and Terry were there, still dressed in sleepwear, their hands cuffed behind their backs, surrounded by jackbooted police in black clothing and helmets with opaque face-shields. Two of the officers picked up Terry and began to dump her unceremoniously into the throbbing ship beside them; she struggled in her thin nightgown, and they laughed huskily, their leather-clad gloves bruising her thighs. Proj started forward and was clubbed to the ground by gun-butts. In a moment they were all cuffed to rails inside the car and it rose with a roar into the air, the courtyard and the brightly lit house vanishing into the dark forest below. Cavallo and Messer watched them go.