My first monster movies were those my father took me to see in my pyjamas at the drive-in. Some, like the original King Kong, were movies he had seen years before, which came back in revival every few years. Others were new movies (This was in the Fifties) that he had noticed advertised in the papers and knew I would love. My favourite, after King Kong of course, was The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, which remained my favourite movie until Jurassic Park changed everything.

But I have fond memories of The Land Unknown, The Creature From the Black Lagoon, Them!, Forbidden Planet, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Thing From Another World, and This Island Earth. The mutant in the last one came closest to actually scaring me. My mother said, "Don't take him to see those things. He'll have nightmares." But by and large the monsters in the movies never frightened me. For one thing, every movie ended with me falling asleep on the way home and being tucked into bed by my father. For another, I was a small, bookish, often sickly child with no sports skills, and I was bullied all the time. The Creature From the Black Lagoon could not hold a candle to the Creature From the Schoolyard.

Of all the movies my parents took me to see, the only scene that triggered such fear that I had to be taken home was the scene in which the cartoon Alice in Wonderland, lost in a dark wood, found a dog with a whisk-broom head sweeping away the path before and behind her. For some reason, I burst into uncontrollable tears. In general, the movie monsters were never near as scary as certain parts of Snow White, Pinocchio, or The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Walt Disney, scaring the bejesus out of little kids since 1937. In fact, Fantasia featured the most spectacular T-Rex on film until you know what Spielberg movie.

My father also introduced me to some of my favourite books. He was a Tarzan fan and made sure I got to know him, as well as Bomba the Jungle Boy. Before I knew it, I was perfectly at home in Pal-ul-don, Barsoom, and Pellucidar. I fear I am still overly fond of that kind of florid, overwrought Victorian prose. But he also introduced me early on to a book entitled The Star-Seekers--one of the many, many stories of generation star ships falling into a superstitious dark age and heading for destruction. I had no idea that I would someday be living on a planet just like that.

The thing about monsters is: They are us. We are the only creatures that slaughter our species with factory efficiency, that raze entire cities with futuristic weapons, that trigger species extinction, that can destroy the Earth. We are the asteroid, the deluge, the plague, the implacable aliens, the Zombie Apocalypse. That's what the movies were trying to warn us about, back in the First Cold War. As Pogo said, "We have met the enemy, and he is us."

The voracious reading and movie-watching my father sparked showed me, before I was even a teenager, the world I would someday live in: space travel, artificial intelligence, self-driving vehicles, global communication, genetic enhancement, organ-legging, diseases eradicated and born again, inter-species dialog, spy-satellites, cyborgs, clones, warriors of the wasteland, drowned cities. I have been musing for a long time on the two contrasting visions of the future: Roddenberry's bright and peaceful galactic federation and the dark apocalyptic dystopias. I thought they were alternative predictions, but now I realize that we will have both at once--2001 above and Mad Max below.

When I finally got around to writing science-fiction, in the late Seventies, I put my characters in that reality. My idea was that Gerard K. O'Neill's Age of Aquarius vision of the High Frontier--orbiting colonies, abundant solar energy, virtually unlimited water and natural resources in the Asteroid Belt, basically free space-shipping with solar sails, and unlimited fusion fuel mined from Jupiter's atmosphere--meant that the High Companies wouldn't need Earth at all anymore, with its troublesome gravity well and depleted resources, and the planet would be left to rot in pollution and poverty. The Whole Earth would be the Third World. I was sure this could happen, though I had no idea--none of us had any idea--just how quickly it would come about. Except the oil companies, of course, who raised all their offshore drilling platforms in the Eighties to compensate for future rising sea-levels, while they tried to convince the rest of us that global warming was a hoax.

I spent a few years sending various books and parts of books to publishers and though I received a number of encouraging personal replies--particularly from Shelly Shapiro of Del Rey Books--nobody actually wanted to publish them. If you want to read them, they are all available to download for free on my website--www.joesworlds.net--as well as here, in Joe's Corner.

I am just a guest here on my sister's website--a visitor from Vermont North, otherwise known as Montreal--because we have nearly the same taste in movies, though she is more tolerant of the low-budget foibles of the genre. My particular areas of expertise are two: movies based on Marvel Comics and Doctor Who.

I read a lot of comic books as a kid. I liked the Scrooge McDuck comics because he took Huey, Dewey, and Louie on epic adventures, and I liked Batman. Also a strange thing called Metal Men. But I usually lost patience with Superman, whose stories I thought stupid. He seemed more interested in keeping his identity secret than in protecting the Earth, and I had nothing but contempt for Lois Lane and Krypto the Superdog. When I was 18, in the early Sixties, I was bagging groceries in a small town in Connecticut and living in a furnished room. On a closet shelf I found an issue of Amazing Stories in which a character named Spider-Man was introduced. I found the story fascinating, but when I decided to hitch-hike to San Francisco with a friend, I put it back in the closet--not the smartest decision of my life.

But in the mid-Sixties I lived in a loft in New York's Chinatown, almost in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge, and nearby was a magazine store that carried all the Marvel titles. They cost a few cents each and every month I bought every superhero title of what they call the Marvel Silver Age (not the westerns and romances, or the war-comics, though I bought Nick Fury when he became an Agent of SHIELD). I loved them. Nobody had a cape except Thor, and most had no secret identities. The Fantastic Four were the first to give that up. Also, I loved the humour and the occasional angst, both of which I later found in Buffy. Besides, their lives changed all the time, and they guest-starred in each other's comics, sometimes as villains.

When I immigrated to Canada in 1967, I took the collection with me as settler's effects, but shortly after that Marvel hit the big time and the titles multiplied out of control. When the Silver Surfer got his own comic, and all the prices shot up, I realized I could not continue collecting every title and quit cold turkey. I kept them for a few years, then sold them and bought a TV. Now I collect every Marvel movie on DVD. I have reviewed them all for you.

Throughout the Sixties, I hardly ever saw TV. Living in furnished rooms on the road, in apartments in Berkeley, San Francisco, New York, and Montreal, I had no intention of buying one of those boxes. Once in a while I would see something on somebody's set that attracted my attention--"What the hell is that?" "Oh, that's Star Trek," or "That's Jason and the Argonauts."--but mostly the box just seemed noisy and stupid. But in the late Eighties, I saw something late at night that changed my life. The program began with a huge machine mining the regolith of some desert planet in a howling sandstorm. Inside, in a corridor filled with dripping pipes, a blue telephone box materialized, screeching like a banshee, out of thin air, and out stepped a man in a long coat, a longer scarf, and a beat-up floppy hat, with a mad mop of curly hair like Harpo Marx and an absolutely insane look in his eye. Behind him came a girl in brief leathers like Sheena, holding a huge knife. I fell instantly in love with all of it. (This just in: it appears that scene never happened like that. I made it up. But I still love it.)

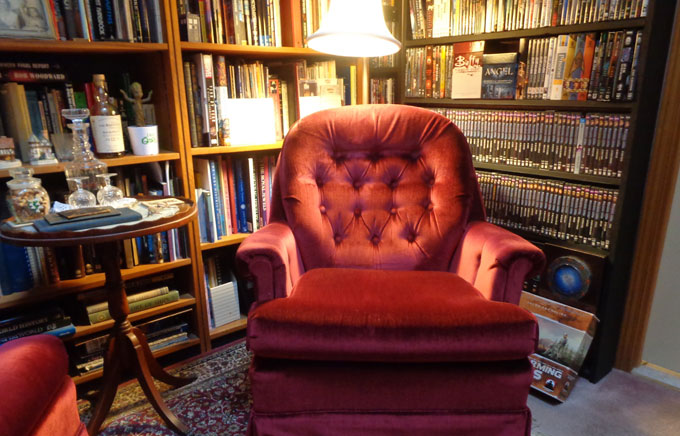

Now I have collected--at great expense and more trouble--all of the extant stories of the Doctor Who series from 1963 to the present. I have reviewed them all for you. I'll review every movie in my collection, if I have time before we have to shut down virtually every major city on the planet and move the population a hundred miles inland, while welcoming the greatest human migration since we walked out of Africa at the Dawn of Man. I notice that the Jehovah's Witnesses have stopped ringing my doorbell and warning me the End is Nigh. I don't know where they went. Maybe they're on a mountain somewhere, waiting for the Mother Ship.

The first Joe's Corner was in the basement of my childhood home, tucked behind the furnace and accessed by a secret door cut in the cardboard back of my mother's old wardrobe. When she discovered this, she scolded me in a stern voice, countered as usual by her smile of admiration for her son's cleverness, though my father was less amused when he had to get to the furnace one day. There, my microscope and chemistry set became a crime-lab and my cap-rifles and revolvers hung on the wall. The communication centre was a collection of broken telephones and a radio that only produced static, though if I listened closely I heard the Mayday calls, the messages from spies, and the boastful taunts of evil enemies. The library of Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs books was there too, for reference. From this headquarters I would battle evil-doers everywhere, well aided by an invisible man, a tiny cowboy that rode in my shirt pocket every day to school, a flying horse that kept pace with the car on Sunday drives, and all the dinosaurs in the upstate New York woods behind the house, whom I could summon to my rescue. Welcome to Joe's Corner.